- 21 April 2000

- One Million Hits, Infinite Hits

- It seems that Internet publishers gauge their success by the number of “hits” their sites receive. (I’m not exactly sure about the technical bits, but in this context I think a “hit” occurs every time a server sends a piece of information out over the Internet that someone has requested.) I suppose advertisers need that sort of information, but monitoring statistics on one’s popularity seems rather childish. I’m a legend in my own mind, so I have no need of public validation or approval.

(As an aside, the perceived need for a large following reminds me of Gore Vidal’s remark: “Some writers take to drink, others take to audiences.”)

Despite my ostentatious charade of aloofness , I must admit that it would be fun to casually mention that my Internet site gets several million hits a day. With that thought in mind, I decided to make a piece that would generate a million hits a day, even if only one person visited.

For my first attempt, I created an Internet sketch that repeated the word “hits” one million times. In one sense, the approach worked: the ten-megabyte file should crash the computer of anyone who tries to look at it. The problem was, for my purposes, that even such a large file technically only generates one hit. I then ran into similar problems when I tried to work with “real” hits. Even by sending the same graphic image over and over again, the sketch that generated one million hits was over five hundred megabytes.

I finally came up with a printed solution in the form of an eight-hundred and two page printed piece, One Million Hits in Eight Hundred Tabs. I was not pleased with the result, though, and decided not to publish a PDF version of the piece.

By the time I went back to the medium of the Internet, I finally realized that I was no longer working with paper. I belatedly understood there was no need to limit myself to a finite number of hits. And so it was that I came up to the Internet-based piece, Infinite Hits.

- 22 April 2000

- An Uneventful Visit With Wayne

- I ran into Wayne Brill again during a fly-by-night visit to Interlochen. It was good to see a dear friend and exceptional mentor again after a long absence.

When I was a student at Interlochen a quarter century ago, Wayne embodied everything I loved about photography. He made beautiful, superbly-crafted prints. He had a closet full of Leicas, Nikons, Rolleis and Hasselblads. I was (and I still am) convinced that he knew everything there was to know about photographic technique.

To me, Wayne was a brilliant anti-teacher: he explained the basics of photography, would patiently answer any question, and he expected—no, make that demanded—technical perfection. No coaxing, no threatening, no tricks, none of the methods one presumably learns when being formally taught how to teach. (I doubt Wayne ever took a formal course on how to teach, but you’ll have to look elsewhere for a biography.) He just sat there, sphinx-like, always questioning, almost never satisfied.

There’s a lot of Wayne in me, even though it certainly wouldn’t appear so to the casual observer. I rarely make photographs any more except to serve as the visual element in image/text pieces; I fear the f64 aesthetic is stuck in the static purgatory of art history. But yet, even when I make a piece that has everything to do with ideas and nothing to do with retinal thrills, I still spend an inordinate amount of time making the best possible image (even if, for example, the print in question is a computer scan of a newspaper lingerie ad printed on a simple laser printer).

And on rare occasions when I do make a photograph, I use my embarrassingly large collection of Leicas, Nikons, Rolleis and Hasselblads. (Wayne once advised me “If you’re stuck, buy a new lens. If you’re still stuck, get a new camera.” I’ve been repeating this for so many years I have no idea if he actually ever said it, but it makes a good anecdote.)

In addition to teaching me to be a good craftsperson (although I’ll never be half as good as he was), Wayne also taught me—if only by example—to never be satisfied with my work. Wayne always seemed in a constant state of agitation about his photographs; they never were and never could be good enough. This may or may not be a paradox, but the impossible demands he put on himself as a photographer never seemed to prevent him from being quite at peace with himself as a human being. G. K. Chesterton was right: “The artistic temperament is a disease that afflicts amateurs.”

His many summers at Ansel Adams’ Yosemite workshops epitomized his approach to life. I can’t imagine that he actually learned much from any of the workshop leaders, including crafty old Ansel. It was the perfect trip: a couple of weeks obsessing about photography while simultaneously enjoying one of the most beautiful spots on the planet.

Wayne’s stories and photographs of the west influenced me deeply. When I graduated from Interlochen, all I wanted to do was make 8x10 contact prints of the western landscape even though I’d never been west of Chicago.

“Haven’t heard from you in a while,” Wayne said as we drove through the piney woods.

“I’m sorry about that; I heard you died in 1992,” I replied. “I even remember the date—wasn’t it the twenty-second of February?”

“Oh that,” Wayne commented. (Wayne uses few words.)

“What happened?” I asked.

“I guess some people got the story wrong.”

“I always thought that death was pretty unambiguous,” I replied.

Wayne just shrugged.

I guess that’s that.

- 23 April 2000

- Jesus’s Miraculous Bronze Underwear

- Today is Easter Sunday, the day when Christians celebrate their savior rising from the dead. According to the bible, Jesus was naked as the day he was born when he returned for his unprecedented encore. That makes perfect sense, clothes are of no use whatsoever to dead people.

Michelangelo Buonarroti also concurred with the biblical record that the recently undead Jesus was unambiguously nude. He said so in his marble sculpture, Risen Christ.

But the idea of the son of a god stripped bare is not universally acknowledged, at least by some of the popes of the Catholic church. For example, go to Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. (You can’t miss it; its basilica is just off the Corso, near the Pantheon.) There, you’ll see an astonishing site: Michelangelo’s half-a-millennium old Christ wearing a relatively new, wondrous, bronze loincloth. The heavy, metal cloth hugs the lord’s loins with no visible means of support whatsoever, clearly a gravity-defying miracle. Hallelujah!

The metal garment in question was commissioned by a pope a few decades ago, and it’s been on and off ever since. That’s not surprising; the introduction of fashion may be inextricably linked to the introduction of clothing.

According to this year’s fashion spotters, Jesus 2000 was again sporting his miraculous bronze underwear. The fashion cognoscenti are divided on predictions for next year’s holy apparel. With myriad plots for a new pope in various stages of gestation, anything could happen.

- 24 April 2000

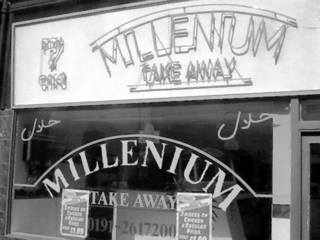

- The Typo of the Millenium

- I ran across a wonderful chip shop today. I didn’t sample any of the food on offer; I knew it was fine without tasting it—you can’t go wrong by boiling potatoes in hot grease, then suffocating them in salt and vinegar.

I love the name of this particular chip shop: Millenium [sic] Take Away. The owners didn’t merely misspell “Millennium”; anyone can do that. (I shouldn’t brag, but I make a different typo almost daily without any conscious effort.)

The proprietors didn’t stop at painting “Millenium” in huge letters on the window, they also did the same thing in neon! That’s my kind of mistake!

If you’re going to make a mistake, make it decisive, make it memorable, make it huge. And, if the opportunity arises, use neon.

- 25 April 2000

- E Plurabis Vomitus

- A famous football player married a famous popular music singer, thus creating a famous couple. The famous couple take themselves very seriously. They also take their fame seriously, so seriously that they’ve designed their own coat of arms.

The result is predictably hideous.

I didn’t get a good look at it; I only remember that is used a lot of tacky “olde English” imagery above the text on the flowing banner: “Love-Friendship.” Or perhaps it said “Friendship-Love”—I didn’t spend a lot of time looking at it.

The silly image really didn’t merit a critique, but it received one anyway. In fact, Stephen Fry gave it one of the best reviews I’ve ever heard: “Sometimes there’s just not enough vomit in the world.”

- 26 April 2000

- Writing About Art

- Sonja asked me what I was writing about.

“The usual,” I replied, “I’m writing about art and the like.”

“Why don’t you write about something you know something about?” Sonja suggested.

That Sonja’s quite the clever one! But then again, so’s Ken Keysey, and so I dug up a relevant quote: “Write what you don’t know. What you know is almost dull. If you had a really interesting life, you almost surely wouldn’t be writing.”

- 27 April 2000

- It Goes Without Saying

- Many years ago Maia forbade me from using the phrase, “it goes without saying.” She told me that she learned that from her college English teacher, who advised her, “if it goes without saying, then don’t say it.”

It goes without saying that I still include the phrase in my arsenal of bad writer’s tools.

- 28 April 2000

- Forgeries Redux

- I’ve got a good story, even if I can’t remember the specifics. That’s not a problem, though; a really good story is greater than merely the sum of its details. And this is such a story.

Once upon a time, there was a very talented forger. His forged paintings fooled almost all the experts almost all the time. As may be inferred from the two “almosts,” though, his less-than-perfect track record led to a few years in prison. The forger was one of those fortunate people whose time in the penitentiary only served to underscore his achievements, and he died a well-respected paint mechanic, not unlike those whose work he copied.

Then the story gets better.

The forger’s work was so highly regarded that collectors started paying large sums of money to own his forgeries. And then the inevitable laws of the marketplace kicked in, and not a few collectors have been shocked to discover their recent acquisitions weren’t original forgeries. They’d been swindled into buying forgeries of forgeries.

Will people never learn? Of course they won’t; that’s what makes the art world’s mercantile follies endlessly entertaining.