- 28 November 2000

- As Far as the Caspian Sea

- I’m on my first trip to India; so I’ve made it as far as the Caspian Sea. This is as good a time as any to learn about a country about which I know next to nothing, hundreds of dollars of inoculations and other precautionary drugs notwithstanding.

I’ve consciously avoided learning anything about India in order to see everything with fresh eyes, although I doubt I can at this point in my life. Indian culture is so pervasive in the west that I already have many preconceived notions about the country, although I fear “stereotypes” would be a more accurate choice of words than “preconceived notions.”

And speaking of words, I see the Hindustan Times uses some words that sound rather quaint, or outdated. Criminals, even violent ones, are “miscreants.” And then there’s “hooch,” which I assume is probably alcohol, possibly bootleg liquor, or, according to my dictionary, perhaps even marijuana.

I can’t help but notice a large photograph of a smiling, jolly Mr. Saddam Hussein that calls my attention to the advertisement in which “Priyanka Overseas Ltd. & its Group Companies Express their solidarity with the People’s Republic of Iraq & Celebrate their 30 years of Association with the Historic Visit of His Excellency Mr. Taha Yassin Ramadhan, Hon’ble Vice President of Iraq & other Hon’ble Members of His Delegation.”

The Government of Delhi Transportation Department also placed an advertisement notifying “the owners and operators of heavy, medium and light goods vehicles (4-wheelers including buses) operating in the Capital Territory of Delhi are once again directed the ensure that their vehicles are fitted with suitable speed governing devices (speed governors) to ensure that the vehicles do not exceed the prescribed limit of 40 km/ and that they remained confined to the bus lane on the extreme left.” My favorite part of the ad, though, was the admonition at the bottom, “Say ‘no’ to plastic bags.” Sounds eminently sensible to me!

I’m not in Europe or North America any more. It’s about time.

- 29 November 2000

- Rhymes with Smelly

- I quite like India so far, at least what I’ve seen of it since landing around midnight last night. Everything is covered in a soft, flattering luminance, thanks to the soupy air pollution in which Delhi stews. The exhaust from a zillion internal combustion engines—flavored with hints of incense, fried food, and cheap cigarettes—makes my eyes water and chaffs my dry, sore throat, but I don’t care. In a day or two the doubtlessly carcinogenic fumes will annoy and perhaps sicken me, but today they’re exotic, as is everything else here.

I said “no thank you” perhaps a hundred times—perhaps more—on a two-hour walk around the city. I declined many offers for “rickshaw” (three-wheeled motor scooters with cab) rides, imitation cobras, shop tours (“Just take two minutes to see what marvels we have!”), drums and unknown musical instruments, various articles of indeterminate provenance, and shoe shines. I turned down the last offer even after the shoe shiner’s unseen accomplice squirted what appeared to be chicken shit on the toe of one of my boots. Is that great marketing or what?!

I easily cleaned what turned out to be artificial chicken shit (?!) off my boot when I returned to my hotel room. It’s my kind of hotel, dingy but clean, with threadbare blankets over clean sheets, an unheated shower, and a reliable electrical outlet for my computer. And all for under twenty dollars (including the twelve-and-a-half percent luxury tax on rooms that cost over ten dollars) a night in the middle of Delhi!

After a cold shower, I’m enjoying sitting in bed under the mosquito netting listening to the musique concrète of New Delhi traffic. I’m looking forward to tapping out many more interrobangs in the next three weeks.

- 30 November 2000

- A Hundred Years After Oscar Wilde

- Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde died a century ago today when he was just a year or two older than me. I suppose it’s good—at least for posterity—to check out at the top of one’s game. I’m glad I’m not there yet.

Since I haven’t tried to learn much about Wilde, I’ll remember him most for his one-liners and other memorable quotes, including these fifteen:

“To look at something is not (necessarily) to see it.”

“The commonest thing is delightful if only one hides it.”

“Art should never try to make itself popular. The public should try to make itself artistic.”

“In Art, the public accepts what has been because they cannot alter it, not because they appreciate it. They swallow their classics whole, and never taste them. A fresh mode of Beauty is absolutely distasteful to them, and whenever it appears they get so angry and bewildered that they always use one of two stupid expressions—one is that the work of art is grossly unintelligible; the other, that the work of art is grossly immoral.”

“All Art is quite useless.”

“Nothing succeeds like excess.”

“Whenever a community or a powerful section of a community, or a government of any kind, attempts to dictate to the artist what he is to do, Art either entirely vanishes, or becomes stereotyped, or degenerates into a low and ignoble form of craft.”

“Bad artists always admire each other’s work.”

“A truth in art is that whose opposite is also true.”

“I’ve put my genius into my life, I’ve only put my talent into my works.”

“In art, good intentions are not of the smallest value. All bad art is the result of good intentions.”

“Photography has the remarkable ability to turn wine into water.”

“Nothing that actually occurs is of the smallest importance.”

“Bad art is a great deal worse than no art at all.”

“I never travel without my diary. One should always have something sensational to read in the train.”

It’s too bad Oscar never made it as far as India. I think he would have had a great time here.

- 1 December 2000

- An Uneventful Chess Game

- If every sports story in every newspaper disappeared forever, I don’t think I’d mind, if only because I don’t think I’d notice. Reading about sports seems as unproductive as reading about sex, which I suppose explains why I’m unequally uninterested in pornography.

And so it is that I am pleasantly surprised to discover myself reading the sports section of a Delhi newspaper that features not only a story about a chess match, but a photograph as well! The photograph shows Viswanathan Anand moving his black pawn to KN3 as his attacker, Viktor Bologan, looks on passively. I’m not sure I would have used the Rossolimo Sicilian defense, but Devangshu Datta, reporting on the match, hypothesized that players were being cautious at the beginning of an important tournament.

(I thought the photograph was rather boring, which isn’t necessarily a criticism of photographer S. Burmaula. I suspect it may be next to impossible to take an interesting photograph of a chess match; even a photograph of Marcel Duchamp playing a nude young woman made for unexceptional viewing.)

The match proved to be as exciting as the photograph, with Bologan and Anand agreeing to a draw after twenty-seven moves. I suppose it’s not really too surprising that there’s not more chess coverage in the sports pages.

- 2 December 2000

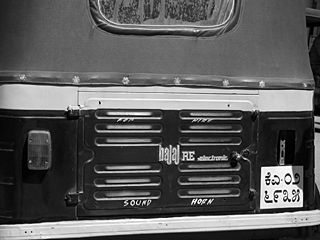

- Delhi Horn Semantics

- Delhi is viscous with crawling traffic, and the traffic is thick with bleating, tinny horns. When I told Rajiv that I couldn’t believe the way the drivers continually honked their horns for no reason at all, Rajiv was kind enough to correct me and explain what the honking actually means.

Rajiv told me that each and every peep of the horn is a two part message, and that the first half of the message is always the same: “I am in this place.” After that, a honk has eight basic meanings:

I am in this place; get out of my way (car).I am in this place; get out of my way (pedestrian).

I am in this place; I am behind you.

I am in this place; I am going to pass you.

I am in this place; I am passing you.

I am in this place; I have passed you.

I am in this place; you arouse my ire.

I am in this place; I am happy to be alive.

- Rajiv said that a Delhi native could distinguish over a hundred separate honks, but that eight was all I needed to learn. In fact, eight turned out to be six more than necessary. Once I learned to recognize “I am in this place, get out of my way (pedestrian),” and “I am in this place, you arouse my ire,” I could ignore the rest of the honking traffic with impunity.

- 3 December 2000

- The Queen Victoria Forms Academy

- The Queen Victoria Forms Academy is one of those dubious institutions the British left behind when Indians gained their independence in 1947. The academy still occupies most of the grand, old, three-story building at the corner of Sansad Marg and Shagat Singh Marg in New Delhi.

I would never have known just how huge the academy is had I not happened to be walking by at 15:30 today when classes ended. Hundreds of students poured out of the building, each of them wearing identical uniforms: brown slacks or skirts, pale green shirts or blouses, and shiny black shoes. Very British, very silly.

Sanjay rolled his eyes when I told him what I’d seen. He went on to explain that the Brits founded the academy in the early 1920s to provide a source of trained clerks and servants for their Indian empire. The sole purpose of the academy was to train students in English penmanship, basic math (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division), and filling out forms.

It’s worth noting that learning the English language was not part of the curriculum. The school’s raison d’être was to churn out mindless bureaucrats to staff a yet-to-be-built administrative infrastructure for yet-to-be-achieved Asian domination. The school’s motto says it all: “To transfer and transmit, with neatness and accuracy.”

Sanjay couldn’t explain why the academy still exists, unchanged, after a half century of independence. He hypothesized that the academy, like so many other things in this ancient land, is just one of the features of the social landscape that’s always been there.

I thought the academy was a ridiculous exercise in bureaucracy until I checked out of my hotel. The clerk opened up one ledger showing room payments, another book showing reservations, a third book with room assignments, and a fourth book showing incidental charges for phone calls, drinks, et cetera. He was operating a complex—albeit perhaps needlessly complex—relational database without the hindrance of an unreliable computer. (I know the phrase “unreliable computer” is repetitiously redundant, but nevertheless chose to keep it.)

“Excuse me,” I asked the man behind the desk, “but did you attend The Queen Victoria Forms Academy?”

“Yes, sir!” he beamed. “I am a graduate of the class of nineteen hundred and eighty-four.”

I had to admit that I’ve never seen lovelier handwriting.

- 4 December 2000

- Lunch with Shankar

- Shankar treated me to a lovely semi-traditional Indian lunch of Bloody Marys (Maries?) and scrumptious fish curry at the Press Club of India this afternoon.

“I’m sorry, Shankar,” I apologized, “but there’s something about being in India that’s put me in a strange and unusually introspective mood. For some reason, I feel like talking about art, life, and the meaning of it all.”

“I believe that you’ll find that it is the fish curry, and not our amazing country per se, that is the cause of your atypical analytical exuberance.”

Whatever. We didn’t spend much time on such minutiae, and quickly moved on to a more freewheeling and wide-ranging conversation.

I’m not sure what precipitated this remark, but at one point Shankar made an interesting admission. “I am a prisoner of the limits of my imagination,” he confided.

“Ah, yes, the imagination,” I echoed. “The imagination is like an anchor; it’s essential when stationary but an impediment at sea.” (I don’t know what possessed me to spout such rubbish; it really must have been the fish curry.)

“Shankar,” I continued, “there’s only one reasonable and honorable thing for a prisoner to do: escape. In your case, you must overpower your guards if you are to be free.”

Shankar looked at me skeptically, as he did every time I opened my mouth. I decided to give him some useful advice before he challenged any of my nonsensical statements.

“What is the imagination but the excessive musing of superfluous brain cells?” I asked rhetorically. “And is there any beverage short of absinthe that kills surplus brain cells more efficiently or pleasantly than vodka?”

And with that, I motioned for the waiter to bring us two more drinks.

Some time later, Shankar and I emerged from the Press Club of India as free, albeit wobbly, men.

- 5 December 2000

- On The Rajdhani Express

- I’m on The Rajdhani Express, somewhere in the middle of a two thousand, four hundred and seventy-two kilometer, thirty-four hour train trip from Delhi to Bangalore. It’s quite pleasant, but then I’m not in the least expensive part of the train.

I’m struck by the contrasts between life on the train and life outside. I’ve seen a lot of rural India, and I’m surprised at how, well, just how rural it is. People tilling their fields with oxen, thatched roofs, goats on the railway station platform, that sort of thing. I was about to write that I was shocked by the extreme poverty, but “poverty” may not be quite the right word.

At a brief stop, I saw an old man walking barefoot along the tracks; he was carrying only a small, tattered bag. When he stopped and reached into the sack, I tried to guess what he’d pull out. Probably his tools, I thought.

I thought wrong. After the old man pulled out his battered old pair of sandals, his bag was apparently empty. He put on the sandals, which appeared to be a size or two too small, and continued on his way.

The reason I hesitate to use the word “poverty” to describe what I’ve seen is that this is more or less how most of the people on this planet live. The dearth of wealth is just that, not necessarily poverty.

I wonder what the old man would make of my observations from an air-conditioned train?

The people who run India’s railways know the same thing about long trips as the people who operate airlines. The purpose of food on a long journey is not primarily nourishment; the body doesn’t consume too much energy when stationary for long periods of time. No, the reason for serving snacks and meals on lengthy journeys is to entertain the prisoners, to provide a third alternative to reading and sleeping.

If this were an airplane, every two or three hours I would expect to see a flight attendant coming down the aisle with a large bag of peanuts, a bag of raisins, and a pair of tweezers, muttering, “Snack? Snack? Snack?” S/he’d then give every passenger who responded affirmatively two peanuts and a raisin.

Bon appétit!

It’s different on the Indian railways, at least in my second-class compartment. Every hour or two, cheerful young men pass through the carriage with another complimentary something or other, ranging from tea, fruit juice, biscuits, and a couple other snacks to huge meals: three entrées, roti or naan bread, fresh fruit, thick, creamy yogurt in individual clay pots, and a few things I couldn’t identify.

I feel uncomfortable. I’m worrying about getting fat from eating too much while I watch slender—but not gaunt or starving—people toiling to survive.

I remember reading a quote from the Victorian era, “To be born an Englishman is to have won first prize in the lottery of life.” When I first read that, I thought the English colonialist who wrote it was an arrogant imperialist. Right now, I’m feeling a bit more forgiving. I can imagine him sitting on a mansion balcony sipping huge gin and tonics and watching the workers on the estate labor from dawn to dusk. He may have been thinking then what I’m thinking now: they don’t deserve that, and I don’t deserve this, either.