| |

- 15 December 2000

- Indian Style and Western Style (Udyan Express)

- I took advantage of both Indian and Western styles aboard the Udyan Express. I used the highly-edited visual notes from these experiences to make Indian Style and Western Style (Udyan Express). The PDF version is the only decent way to view this piece; the notebook illustration is, as always, just a gratuitous image.

- 16 December 2000

- An Uncharitable and Unfair Review

- “What a bunch of retro-traditional crap!” was my uncharitable—and admittedly unfair—review of the half-dozen art galleries Vilasrao and I visited in Mumbai before I gave up. (That’s not really a slur against Indian art in general or Mumbai galleries in particular; a half-dozen galleries is about all I can tolerate on most days in any city.)

“So where would a thirsty fellow find a bottle of Kingfisher Strong Premium Beer to wash down some bad art?” I asked Vilasrao. “That’s even more hypocritical than usual, even for you,” he scoffed. “I’ve heard your stuff described as much worse than mere crap.” “Exactly my point,” I replied. “Now that I’ve taken crap to a new plane, going back is even boringer than before.” Vilasrao rolled his eyes, a gesture I usually interpret as surrender. After Vilasrao and I agreed to disagree about art and agree on Kingfisher Strong Premium Beer, we had a very pleasant afternoon.

- 17 December 2000

- Gayatri Mirza’s Big Break

- Gayatri Mirza’s story is one of those literal rags-to-riches stories that makes India so very Indian.

Mirza was working as a unit in a human conveyer belt on a construction site next to one of Mumbai’s largest art galleries. (From what I’ve seen in passing, women at Indian construction sites are apparently relegated to carrying improbably large loads of bricks or debris balanced on their heads.) According to the story Priyanka told me, a western man in a suit approached the construction site foreman and asked who had left a bag and a half of rubbish and a pile of other detritus beside the gallery. The foreman apologized profusely, and pointed out Mirza as the culprit. Well, it turns out that the man in the suit was a Very Important Curator from a Very Important Museum. (Priyanka couldn’t remember whether it was the Museum of Modern Art or the Guggenheim, or maybe the Whitney.) The curator approached Mirza and asked her a number of esoteric questions about the debris, which he thought was an art installation addressing inequities in contemporary Indian society. Mirza, who spoke little English, replied to most of his remarks with, “I cannot use words to answer.” Mirza’s silence—always a good policy for an artist—lead the curator to conclude that “her work speaks for itself.” Mirza ended up accepting a lucrative commission to install a site-specific piece in New York. She more or less repeated what she’d done before—always a good commercial policy for an artist—and hauled the contents of seventeen of the museum’s waste baskets into an empty gallery. Chance smiled on Mirza’s decision. It turned out that the trash contained a number of disposable diapers (?!) as well as a tray of sashimi that was rejected by a visiting vegan. In lay terms, the gallery stank like a Calcutta slum on a hot day. In the critical artspeak of the reviewer from the Times, “Mirza’s attention to the olfactory senses reminded western viewers that there’s more to ‘multimedia’ than just sight and sound.” The trash also contained a Glock pistol, which the New York Police Department tried to confiscate as evidence in the unsolved murder of a petty drug dealer. The museum refused, citing the artist’s freedom of speech rights. The ensuing court battle turned out to be a publicity windfall for Mirza. Mirza’s first “installation” is protected under a glass canopy outside Mumbai’s Terrace Art Gallery. No one is quite sure about the whereabouts of the artist herself; rumor has it that she’s avoiding the commercial art world—always a good policy for an artist.

- 18 December 2000

- Disposable Toilet Paper

- I’ve been enjoying some yummy peppers and spices during my trip to India, but it hasn’t been easy. All the Indian restaurants want to serve me bland food. Even though I always I ask for “extra hot,” or “very spicy” dishes, I’m sure the waiters take one look at my pasty, white face and tell the chef to serve the foreigner the low-octane version. Even so, I have yet to encounter a meal that couldn’t be saved with generous dollops of the chili pickle I carry with me.

As a result of my culinary excesses—or perhaps an unrecognized allergy—my nose has been running a lot since I got here. That’s why I’m not surprised by all the stashes of toilet paper I’m finding among my things: I never learned to blow my nose without the use of some sort of processed cellulose pulp. It’s a dependence most Indians don’t seem to share. Every morning, I listen in amazement as the natives make an incredibly wide range of guttural gasping and honking sounds as they collect and expel all the mucous that’s accumulated overnight. I think the Indians have the right idea. It seems silly to rely on paper for the most basic biological functions. Toilet paper here is something of a luxury—which I suppose it is—and is marketed accordingly. The packaging on the roll of Lovett Toilet Tissues I bought features a creepy photograph of a man standing outside the toilet stall in use by a little girl. This is the first label I’ve seen that extolls the virtues of a roll of toilet paper at such length: - Made from Ultra Soft VIRGIN PULP TISSUES, Imported from APP Ltd., Singapore

- Gentle to skin

- Super absorbent

- Environment friendly

- Untouched by hand

- Internationally acclaimed quality

- Hygienic Economical, Disposable

Imported, disposable toilet paper seems like the right idea in the wrong place, or possibly the reverse.

- 19 December 2000

- Oh Surly Flight Attendant, Please Don’t Go

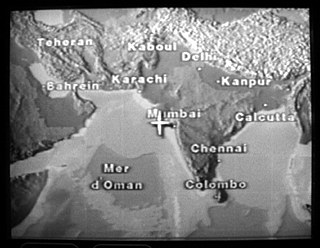

- I’m actually enjoying a flight on one of the world’s very worst airlines, Air France. After three weeks in India, the shoddy airline’s decrepit jet feels almost like Western, first-world transportation.

To celebrate over some cheap but cheerful miniature bottles of acidic French Merlot, I’ve composed a new song. Drinking, on a jet plane,

Don’t know when I will drink again,

Oh surly flight attendant,

Please don’t go.

- My singing, and my polite but firm requests for another tiny bottle of wine, has captured the attention of the surly flight attendant. Sadly, it turns out that she is not among the fans of my musical innovations.

“Monsieur!” she reprimanded, “We do not joke about drinking.” “Ah, but we who are not French drink about joking,” I explained. “And are we not the paying passenger, and are you not—how do you say—la grande vin femme de chambre du avion?” And with that, she stalked off. She returned a couple minutes later with four wee bottles of Merlot, slammed them on my tray—whacka! whacka! whacka! whacka!—then huffed off down the aisle. Oh well. Drinking, on a jet plane,

Don’t know when I will drink again,

Oh surly flight attendant,

Please don’t go.

- 20 December 2000

- Indian Visual Clichés Successfully Avoided

- In retrospect, the biggest surprise of my first trip to India is how very few photographs I made. In the past, I’ve responded to my first visit to a new country by seeing things I’ll never see again. For example, I still like the many photographs I made on my first trip to France fifteen years ago, but I haven’t made a Gallic image worth keeping on any of my subsequent trips.

I know this is a tautology, but I was looking forward to my first trip to India as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see that country for the first time. I ended up only taking a dozen photographs or so, and most of those were illustrations of one sort or another for my notebook. Although I did see lots of interesting sights, I thought that most of the photographs I could have made would have just been clichés. These include “land of many contrasts” images, (cattle sleeping in front of office towers, Indians in fashionable Western clothes talking on mobile phones as they walk past beggars—with and without leprosy), misspelled English signs (Beware of Hoodlumps, Kentacky Chicken Shack), religious imagery and/or people in apparel I didn’t understand, poverty, filth, et cetera. There’s a lot more to India than the obvious clichés. I’m not sure what that is, perhaps I’ll find it later. Or perhaps not. In any case, who wants to see—let alone create—more clichés?

- 21 December 2000

- Where’s Shiva When You Need Him?

- Although I was ready to leave India after three weeks of yummy curries floating by in streams of Kingfisher Strong Premium Beer, it appears I should have spent one more week there. I’d forgotten just how wretched the alleged “holiday” season is, an oversight just about every merchant is happy to remedy with admonitions to consume more, accompanied by saccharine sentiments. That, and the bitter winter winds, almost make me look forward to fire and brimstone.

By contrast, I quite enjoyed all the Hindu festivities in India. I heard amazing drummers on the streets, and saw some really great television shows. (I’ve never used the phrase “really great television” before, and shall probably never use it again.) I only heard a Christmas jingle once. An Indian cab driver had wired his car to play a tinny version of Jingle Bells when he reversed. Another cab driver had configured his cab to play Happy Birthday when backing up, both tunes made a nice counterpoint to all the horns that blared out the first couple of bars to the theme from The Twilight Zone. Where’s Shiva when you need him? He’d look even better with Santa’s cranium added to his necklace of skulls.

- 22 December 2000

- Poodles in the Manger

- Aaron and Sadie are tolerating the relentless Christmas hyperbole better than I am; perhaps it’s because they’re Jewish. And perhaps why they insisted that we go out of our way to examine yet another model of the nativity scene.

“Let’s see,” said Aaron, “There’s Jesus; there’s Mary; there are the three wise men. But tell me about the poodles, these I haven’t heard about.” “Poodles are a traditional Christian symbol of humanity’s folly in attempting to dominate the animal kingdom,” I explained. “The deformed dogs represent the presence of Satan, the repulsive triumph of evil over good.” Aaron and Sadie nodded, then suggested we head back to the lab. I still haven’t told them that the critters they thought were poodles were supposed to be sheep.

last transition | index | next transition

©2000 David Glenn Rinehart

| |